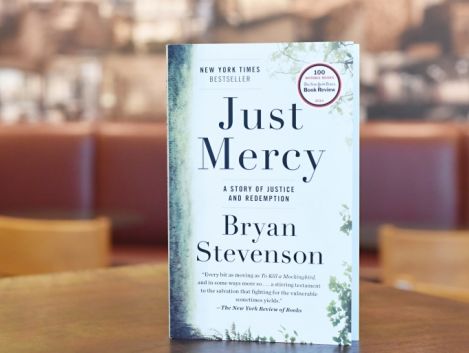

SEATTLE, 2015-8-17— /EPR Retail News/ — Bryan Stevenson’s award-winning New York Times bestseller “Just Mercy” will be available in participating U.S. Starbucks stores beginning August 18. Starbucks is proud to partner with Stevenson as a reflection of its commitment to create opportunities for all by raising greater awareness, empathy and understanding on the issues concerning Americans when it comes to inequality of opportunity.

Stevenson has earned renown as the founder and executive director of the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). The private, nonprofit organization provides legal representation to indigent defendants and prisoners who have been denied fair treatment in the legal system. Starbucks will donate 100 percent of the profits from book sales in its stores to EJI.

The 55-year-old Delaware native is a graduate of Harvard Law School and Harvard School of Government, and is a professor at New York University School of Law. He started EJI in 1989. The nonprofit has since won reversals, relief or release for over 115 wrongly condemned prisoners on death row.

Stevenson, who is also a professor of law at the New York University School of Law, has received numerous honors, including the MacArthur Foundation “Genius” grant and the Olaf Palme Prize for international human rights.

In addition, “Just Mercy” was named by TIME magazine as one of the “10 Best Books of Nonfiction” for 2014, a Notable Book of 2014 by the New York Times, and it won the 2015 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction, among many other awards.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu wrote in Vanity Fair: “It’s leaders like Stevenson who shape the arc of the moral universe. Justice needs champions, and Bryan Stevenson is such a champion.”

The Starbucks Newsroom talked with Bryan Stevenson about “Just Mercy,” and his passion for equal justice and opportunity.

This feels like a momentous moment in American race relations. Do you think history will judge this year-long stretch as a significant juncture?

It depends on what happens. For the last year there has been heightened awareness to the continued frustration and despair in many communities of color about the continuing lack of progress on racial justice issues that’s been manifest in the response to the shootings by police in Ferguson and New York and Cleveland and Baltimore. And so there’s been a growing awareness and many people are dissatisfied, to the point that they’re becoming active in protests. I think the shooting in Charleston concretized a longstanding fear that the narrative of racial difference that we have all inherited in this country is still dangerous, still a menace and still a threat to the kind of community we want to live in. I think the confluence of those two things has put attention on these issues in ways that we haven’t seen in a while. Whether it turns out to be a momentous era depends on what happens.

There seems to be some movement to revisit the issue of mass incarceration in America on both sides of the political divide. Given your legal expertise, what are your observations on that subject?

I do think we have turned a corner on the acceptability of over-incarceration and excessive punishment. I think people from both political parties now recognize we have too many people in prison – too many folks who are not a threat to public safety. It’s too expensive. It’s not fair, it’s not just and it’s not consistent with the values and norms that we articulate for ourselves as a nation. I do think that this is a moment for reform after 40 years of fear and anger that have conspired to create a different America with us now having the highest incarceration rate in the world. We’re in a different place than we’ve ever been before and it is hopeful to me that people from both political parties are speaking out against this problem.

In December, President Obama appointed you to the Task Force on 21st Century Policing. And in your book, “Just Mercy,” you tell the story of an encounter with police where you had to fight off an impulse to flee, even though you’d done nothing wrong and were facing a gun. That must have resonated with you at times in the last year.

It has. I think one of the great burdens that you feel when you’re acutely aware of the way in which this presumption of dangerousness and guilt to society placed on men of color and the problem it creates is that you worry about people. I worry about my nephews. I worry about the young people I see in the streets. Do they know how to manage a situation like that? If it could happen to me in my 20s with a Harvard law degree and some experience as a police misconduct attorney, then I have no reason to believe other men of color are going to be exempt from that.

And so that is the great burden of being aware of these issues. You begin to really worry about how to prepare both the population of kids that are going to be in these really dangerous situations and change the culture of policing so that they’re less comfortable, less willing, less likely to pull a weapon when they’re dealing with people who are not a threat. Yeah, more than anything what has concerned me is that, if you’re being a good parent or good teacher or good advocate, you have to prepare this whole population of kids to manage these situations.

We tell people how to drive. We tell them how to safely navigate wildlife in particular regions of the country where there are threats. We tell them not to talk to strangers. But when you have to tell them how to safely survive when you encounter the police who are going to think you’re dangerous and guilty, you begin to feel really burdened in ways you shouldn’t.

Your book is framed by the extraordinary story of Walter McMillian’s murder case, in which the defendant somehow ended up on death row before he’d even been tried. Mr. McMillian made this comment when he was in a particularly demoralized state: “They know I didn’t do this. They just can’t admit that they were wrong.” At some point, was that the nut of the conspiracy against him? And, if so, does that observation resonate with you beyond the McMillian case?

Yeah, I think that is it. I think that, much like our collective history around these issues with racial justice, we have a hard time acknowledging our failings, our shortcomings. I think some people believe if you admit or acknowledge any problem, then everybody questions everything and it’s a disaster. So you just never acknowledge mistakes.

I think it’s comfortable. It’s convenient to assume you always arrest the guilty. And you certainly always convict the guilty. And if the death penalty has been imposed, there’s no question the person is guilty. To acknowledge that’s not the case is unnerving enough that some people won’t do it. I think that continues to be a problem.

That mindset, what Mr. McMillian said, is exactly what we were dealing with in the Anthony Ray Hinton case just this year. The reason why we couldn’t get the state to acknowledge his innocence last year was because there was this resistance to admitting that they’d done something wrong. If not for the Supreme Court’s intervention, which required the case to be overturned, he’d still be on death row, even though the evidence of innocence was just as compelling 15 years ago.

So creating a culture where you acknowledge mistakes – that you are eager to correct problems – is going to be one of the challenges that we face as we move forward. Can we get prosecutors and judges and police officers who understand that they become more respected when they acknowledge there’s a problem than when they deny it? Like I keep saying to people, I don’t know any good intimate relationships – marriage relationships – where people are uncomfortable acknowledging, “I did something wrong. I’m sorry.” People who are in a relationship where they aren’t ever saying I’m sorry are the ones I worry about, to be honest. And yet our criminal justice has been organized around this premise that somehow, for a lot of people, you never admit a mistake and never apologize. That’s something that sets us up for these tragedies like the McMillian case or the Hinton case

Addressing inequality in the criminal justice system and beyond would appear to be your life’s work. Certainly, given your background, there were more lucrative avenues you could have explored. Why do you think you chose this course in life?

I guess I’ve always felt like I need to do what’s important and right rather than what’s lucrative. The one advantage of coming up the way I came is I never expected to be affluent or well-paid. That wasn’t a marker of anything important to me. The people around me who I most respected were people who just seemed to have wisdom shaped by proximity to the things that mattered to them.

My grandmother and people in my family who I admired were people who understood this history and felt compelled to challenge the things that needed to be challenged. I think I just grew up with this orientation that doing the right thing even when the right thing is hard will yield more fulfillment and satisfaction than doing things that are just lucrative. It’s not that I’m against things that are money-generating. It’s just that I knew there was something rich in this life of engagement with things I care deeply about.

I’m also just better at doing the things I care about. Some people can make an extra effort and just create an excellent product, regardless of what the issue is [and] despite their disengagement with the topic. I really work best, function best, do best when I care deeply about what I’m doing.

In “Just Mercy” you use the framework of Walter McMillian’s situation as a leaping-off point to address many elements of race in America and a lot of it is pretty disheartening. Are there developments that make you optimistic?

I continue to believe that we are perhaps on the verge of beginning a conversation that will really be transformational. I think that what the truth does is liberate you. It cuts you free. And if we become more truthful about our history, I just think there are going to be all kinds of powerful outcomes.

I do yearn for an era where children are born to a country where they’re not burdened by this narrative of racial difference. Where the legacy of racial inequality has been addressed, so that we’re attuned to it in a way that we can move forward. I don’t think that being born in Germany now makes you more likely to be anti-Semitic than being born someplace else in Europe, but that’s only because there has been some recognition about how this horrific hatred and misguided orientation toward religious minorities corrupted that society.

You don’t want that corruption. It’s like learning that you shouldn’t smoke or something disruptive. People before you just did it without thinking and you now know something they didn’t and your relationship to that is very different. We haven’t really done that with regards to race, but I think if we did, we could see radical improvement, radical progress. That excites me and makes me hopeful.

We could still be mired down in issues that would make it impossible to talk about changing the landscape and confronting this narrative. We could be dealing with legal structures that authorize racial hierarchy. We’ve largely succeeded in dismantling those things. That creates an opportunity to talk about the psychic and sociological and emotional features of this longstanding problem.

I am hopeful. I have to be. You have to be willing to believe things you haven’t seen to do any of the things we’ve done. If you were a slave, you had to believe you could be free. If you grew up with segregation, you had to believe there would be a time when those laws would no longer be tolerated. I think that’s true for this generation just like it was for past generations.

Bryan Stevenson’s photo by Nina Subin

For more information on this news release, contact the Starbucks Newsroom.

###